This beautiful exercise book is a small donation that turned out to have a big history – both of its author and of the two sisters whose school it came from. It isn’t often we get handed something that is truly unique but this is one of those circumstances. The sad tale of Elizabeth Ann Bakes and the riches-to-rags-to-riches story of the Hudson sisters is now here to discover.

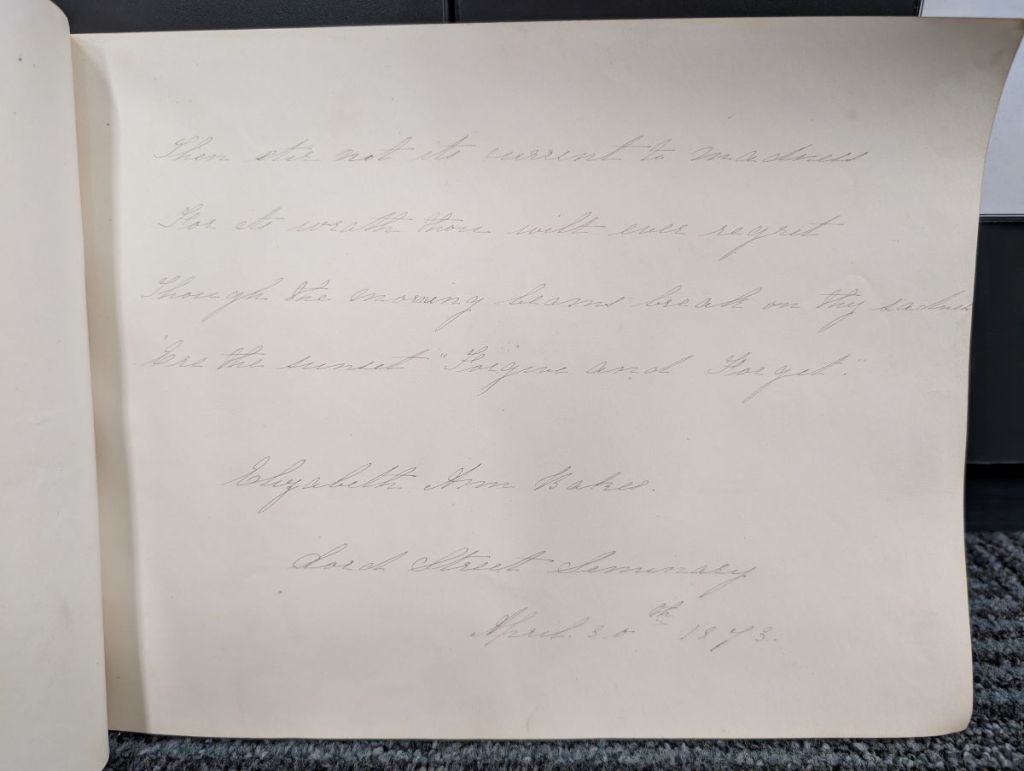

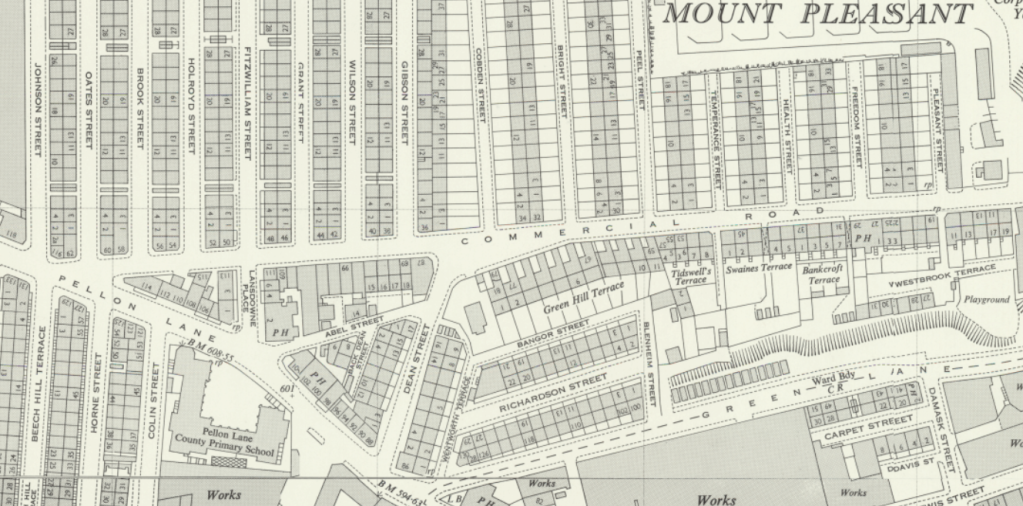

First, the story of its owner. Elizabeth Ann Bakes was born in the summer of 1858 to Joshua Frederick Oates Bakes – get the jokes about delicious oat bakes out of your head before you continue, we know you’re making them – and his wife Sarah (formerly Taylor) Bakes. She was the eldest of only two daughters they would have; Mary Ellen would follow four years later. The Bakes lived at 2 Wentworth Terrace, the first of many “lost” addresses in this story. Wentworth Terrace used to be sandwiched between what is now Richmond Road and Mount Pleasant Road, just off Pellon Lane, and appears on maps as early as 1850. They were nice houses and The Bakes were comfortable people. Joshua was an insurance agent for Prudential and did good business. And this meant that Elizabeth Ann was able to attend the Misses Hudson’s school. This penmanship exercise book is dated 1873 inside and was printed especially for students of the school. Each exercise is signed with Elizabeth Ann’s full name and the date.

She was a good student and when we get to the 1881 Census her occupation is given as assistant elementary school teacher.

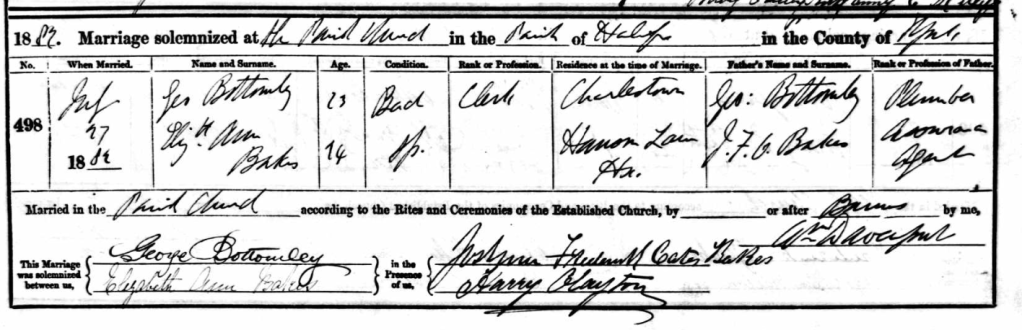

Sarah Taylor Bakes died in 1881 and the following year Elizabeth Ann got married. Her husband was George Bottomley, a clerk who may or may not have worked for or known her father Joshua. He and Joshua were certainly close enough for George to be one of the witnesses to his second marriage in 1888 to Sarah Ann Camp. Meanwhile Elizabeth Ann gave up on her teaching career to raise a family as was standard practice in those days, when more often than not married women were not permitted to be employed as school teachers in most local authority schools. She and George had six children together – two sons, George and Harold, and then four daughters in quick succession. The Bottomleys settled not far from the Bakeses at 13 Commercial Road, in a row of terrace again lost to time and modernisation – what is now Mount Pleasant Road itself, and the houses on that side now replaced by Beech Hill School.

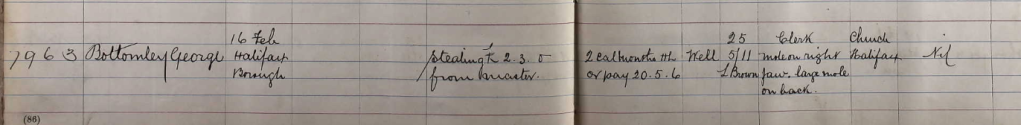

Their marriage was a short one and possibly also a rocky one; a George Bottomley, clerk, aged 25, from Halifax, was convicted in 1885 of embezzling money from his employer. All the facts within this court record match our George here, but was it him? If so it certainly didn’t hurt his relationship with his father in law, so perhaps not. This is the trouble with using public records and newspapers – you can only get so far sometimes and find yourself guessing at what the gaps mean.

What we do know is that George died on March 1st 1897. A £3 fee to the GRO revealed the cause to be pulmonary tuberculosis. To make matter worse, their daughter Doris died on June 1st aged 3. Another £3 tells us it was a similar cause of death; in her case, tubercular meningitis.

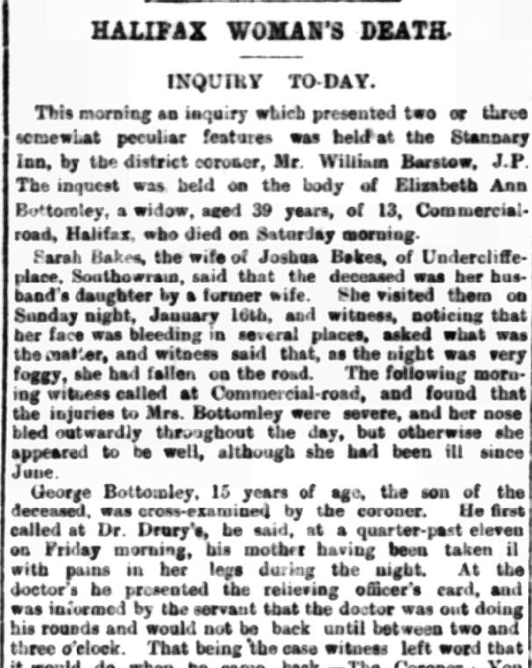

Both were sorely, painfully missed. We know that because Elizabeth Ann became seriously unwell afterwards. It would have been hard for her with six children aged 14 and under, the youngest less than a year old when George died, and then the double whammy of losing her second-youngest daughter so quickly afterwards. She had financial support but with her mother gone there was something lacking in terms of emotional support there. By January 1898 she was suffering from a number of suspicious health complaints including an enlarged liver and inflammation of the heart, and was regularly being found with cuts and bruises on her from falling over or walking into things. That same month she died, and her stepmother and poor eldest son had to give evidence about her sudden death at a coroner’s inquest. Inquests were public affairs in those days and covered extensively in local newspapers, so the details – gory, insensitive, scandalous – were public knowledge. Given this, great pains were gone to during testimony given to not explicitly state what was wrong with Elizabeth Ann beyond “chronic dyspepsia”, but we can make some guesses.

Between the doctor stating he had been treating her for some time and that he had “formed an opinion of what was the matter with her some time before”, his lack of haste in attending as it seemed to be typical-for-her symptoms of pain in her legs and vomiting, and the particular physical symptoms left behind that were discovered during the autopsy, it looks like poor Elizabeth Ann may have turned to alcohol after George and Doris’s death. Or perhaps she suffered from an autoimmune disease or untreated hepatitis that wreaked havoc on her organs and which was made worse by her grief. Maybe the doctor made the same assumption we initially did and thought her illness was due to alcohol abuse and never investigated further. You could maybe even condense everything down into a simple statement: she died of a broken heart. She was only 39 years old.

The Bottomleys are buried at All Saints, Salterhebble, along with George’s parents and his sister Annie who had all predeceased him. Joshua and Sarah Ann Bakes took in the remaining children.

Now, what about the school itself, where Elizabeth Ann learned to write so beautifully? Now it’s time to find out where the Misses Hudson came from and what their lives were like. This was difficult because as mentioned at the very beginning, there was no record in our collection here at Local Studies of their school, and surprisingly nothing online either. Who were they?

James Hudson was a calico printer from Rossendale who, along with his wife Mary and seven of their children, had settled in Halifax by 1851. The family had previously lived at Gale House in Littleborough and James had a complicated financial history, going bankrupt repeatedly from 1827 through 1834. The business rallied but in 1845 it all came crashing down once more, with not only bankruptcy proceedings against him and his business partner but also civil suits against him for unpaid wages and a criminal case against him for slapping a tax collector! So it’s not a surprise that he moved what was left of his business, and his family, from the Gale Print Works over to Halifax.

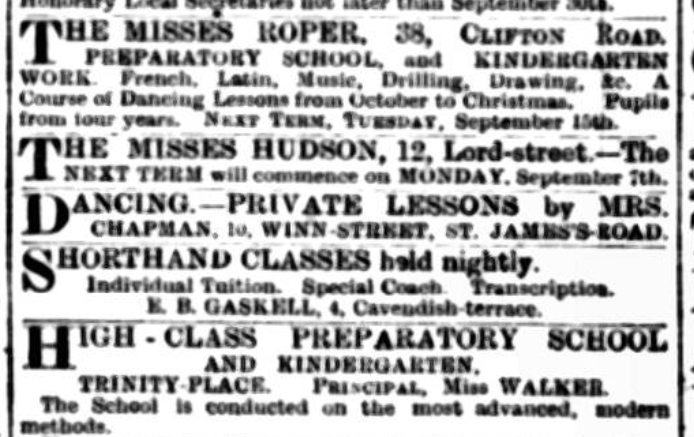

Mary, formerly Bamford, had originally hailed from Handle Hall in Calderbrook and was educated enough to sign her name on the marriage banns from 1823; between this and James’s (relative) wealth it’s no surprise that all the female children received an education. And so, many years later, the Misses Hudsons Seminary was born. Sophia Leonora, born in 1828, and Sarah Elizabeth, born in 1838, became schoolmistresses. Mary Ellen, born in 1843, became a music teacher, neatly rounding out the skill set required to run what must have been a very posh, very refined school for gentle young women born to families of moderate means, like Elizabeth Ann Bakes.

And the money must have helped the family get back on its feet and stay on its feet, especially after James Hudson died in 1871 with an estate totalling less than £31 (and which remained unsettled until 1886). After all, it isn’t cheap to get these lovely, personalised exercise books printed, and they must have had a good enough reputation to be able to advertise quietly in the papers for students and never go without pupils. They also seem to have avoided any scandals that might have found them named in the newspapers. You’d hope so but it wasn’t always a guarantee! It’s just a shame that there’s such a large gap in the record about the sisters and their school. What other classes were taught? What did girls leaving the school take with them? Were there really no notable pupils who later referred to the education they received at the hands of the Hudsons? Apparently not. All we have is this beautiful little book.

Mary Ellen married Oswald Parsons in 1880 and set out for Wales, so this left Sophia and Sarah in charge of the school. It continued to thrive despite strong competition from a host of other small preparatory schools in the Halifax area. For another sixteen years the “Misses Hudson” advertised the start dates for each term in the Halifax newspapers as they rolled round. Finally, in autumn 1896, the final notice appeared.

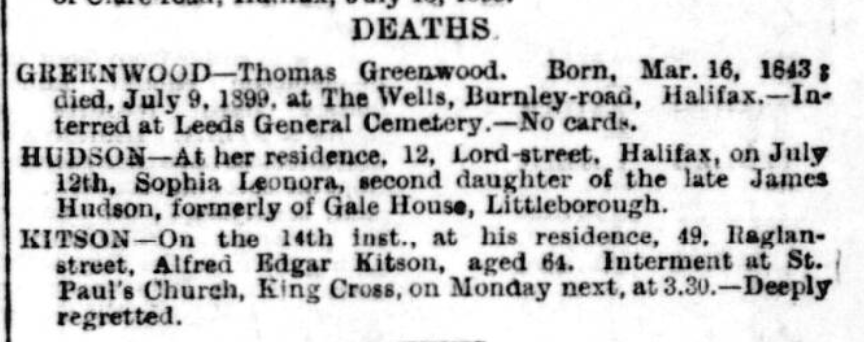

The two sisters had carried on alone in work and eventually alone together, with mother Mary dying in 1885 and the sisters left with only each other and a servant for company. In June 1897 Sarah died, and the school was closed for good. She left behind £738 for Sophia. Sophia’s death followed a few years later in July 1899 and her estate was, unsurprisingly, significantly higher at £1735. Sophia’s solicitors were left with probate, there apparently being no family left to administer the estate. To the very end the family’s connection to Gale House was included as a reminder of the moneyed origins of the family, even if the money Sophia died with was earned wholly under her and Sarah’s own steam, independently of their father.

The question of who saved this book is an interesting one. It was clearly a relic of a happy time for someone; one of the Hudson sisters, or Elizabeth Ann? It’s with us now though, and will stay in our collection, a reminder of both one young woman’s tragic losses and two other young women’s hard-won successes.